The Art of Japanese Coffee: Getting to Know Timeless Kissatens

In Tokyo, tucked away in narrow alleyways, upstairs, underground, and overhead are hundreds of small coffee shops, each with its own distinct approach to roasting, brewing, and decor. These shops have become a personal obsession of mine and other coffee snobs the world over. Called Kissatens, these cafes saw their heyday in the post-war economic boom. And while there are just as many high concept third wave coffee shops available to serve your coffee needs in the world’s largest city. Many Kissatens are untouched by progress and still able to be experienced in the same manner as they have for decades.

The Kissaten resides within a Venn diagram where one circle represents retro-fied Showa era spaces, one circle the Japanese pursuit of excellence (Kodawari), and in the final circle is the Meiji era concept Wakon Yosai, meaning Eastern Spirt, Western Trade.

Coffee was introduced to Japan during the Edo period when the country remained closed for trade except for specified areas in the Nagasaki Prefecture. It was here, in the mid-17th century, that coffee was introduced by Dutch and Portuguese traders. Later, it gained popularity with farmers in the countryside in the form of Koohiito, small balls of coffee, and sticky sugar.

Meiji Restoration

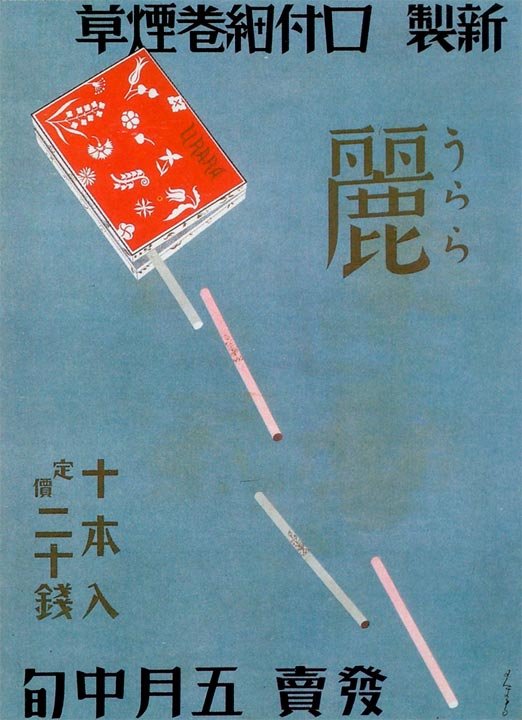

Old Advertisement: “Bring Your Family” to Brazil.

Any history of Japan emphasizes the divide between life in the country before and after the Meiji Restoration. When, in the late 19th century, Japan launched international trade initiatives, one of the first being a trade treaty with Brazil focused on developing the coffee industry.

Even today, as I hop around from Kissa to Kissa, Brazilian coffee is ubiquitously advertised as the base bean for most of the house blends, called “Blendos”. Cafe Paulista, the oldest coffee shop in Tokyo opened its doors in 1911 and continues to serve only Brazilian coffee.

As the trades of this treaty began crossing the seas, so did Japanese laborers who migrated to Brazil to work on its thriving coffee farms. Over the decades following the 1895 treaty, many of these workers went on to own and operate their own coffee plantations and were eager to bring their beans back home.

The Interior of the current Ginza Location of Cafe Paulista

In 1911, businessman Ryo Mizuno opened "Cafe Paulista" in Tokyo's Ginza district, selling Brazilian coffee, expanding to 22 locations throughout Japan and as far as Shanghai, becoming one of the world's first coffee chains. Starting in the Taisho era (1912-1926) and peaking during the Showa Era (1926-1989), Kissatens sprouted all over the country as a new type of social space with endless variations, such as the jun-kissa (a "pure cafe" serving only nonalcoholic beverages) or the jazu-kissa (a cafe playing the latest jazz records).

Antique Advertisement the Original Cafe Paulista next to an Ad on immigration opportunities in Brazil.

While mid-century innovations aimed to make coffee faster and more standardized, others in Japan were focused on slowing down the extraction process to allow for microscopic attention to perfection.

Mamoru Taguchi, owner of Tokyo's Cafe Bach, began roasting his own beans in the early 1970s and developing his philosophy of kohi-gaku, or "coffee-ology," which included detailed classifications of roast types, brewing methods, and more.

Others in traditional Kissatens and more modern cafes began to formalize their traditions or experiment with new ones, such as the slow drip-by-drip cold-brewing pioneered in Kyoto. Similar to the story of denim and blue jeans in Japan, Japanese connoisseurs adopted a "foreign" cultural object and gradually refined it into an art form rather than merely a fashion statement. Wakon Yosai, Eastern Spirt, Western Trade.

Wakon Yosai

Take the success story of Hibiki whiskey. Shinjiro Torri, who founded the Suntory distillery, took his fondness for fine highland scotch and imbued the process with Japanese philosophies of harmony with nature. His whiskey would be scotch but his scotch would be purely Japanese. 3 different distilleries were built in three separate environments in Japan, each one imbued with the natural characteristics of the area.

“He dreamt of creating subtle, refined, yet complex whisky that would suit the delicate palate of the Japanese and enhance their dining experience.”

His Hibiki line was first released in 1989, but it wasn’t well known until 2011 when it shocked the whiskey world and was awarded “World’s Best Blended Whisky”. It has since won that prize six times, even as the bottle price has doubled. In recent years Hibiki wasn’t able to be nominated because the original distillery had to shut down due to extreme demand. The new distillery was built with no compromise to vision or quality and a bottle today remains in high demand around the globe.

An Antique Map of Nagasaki Prefecture in 1821

How Coffee Arrived in Japan

Nagasaki is nestled in a valley surrounded by small islands on the shores of the East China Sea. For decades it operated as a far-off piece of Japan where trickles of the outside world made their way ashore during centuries of Sakoku Jidai (the closed period before the Meiji restoration). Off the coast of Nagasaki is a small island called Dejima where in 1570, the Portuguese and later the Dutch set up the only official trade post in Edo-era Japan.

Until the late 1800’s, Dejima was the single window the world had into Japan. Conversely, the only access average Edo people had to rest to the world were the artifacts and rumors brought from the island by the laborers and representatives allowed to conduct business on Dejima.

After Japan concluded an exclusive trade contract with the Dutch East India Company in 1601, the French were allowed to join the Dutch in trading from Dejima. Specified Japanese citizens were allowed onto the island, fellow merchants, translators but most importantly for the story of coffee, sex workers.

According to municipal records, the sex workers of Nagasaki would visit foreign clients on Dejima and bring back gifts from the “red haired people”. Candles, soaps, chocolate, salts - but the prize commodity was “kahii”. Brewed like a tea and served with heaping ladles of honey, the stimulant properties of kahii allowed them to stay sharp late into the night, protect themselves from theft and a clientele prone to depart without paying.

Kahii (coffee) is also shown in Shogunate documentation as special gifts sent from Daimyo to Daimyo. (Provincial feudal lords)

There is documentation of coffee being used medically near Nagasaki and as far as Kyoto. One Dutch doctor, Philipp Franze Von Siebold had accompanied the Dutch East India Company on tours of Java, Sumatra, Macao and Japan where he was able to gain traction selling Coffee to Chinese and Japanese herbalists who found the bitter taste reminiscent of many medicinal herbs and found it helpful to prescribed for stomach ailments.

Coffee remained an exotic commodity, part of a glimpse into Western culture until the end of the Edo period (1868) and the rapid expansionist policies of the Meiji Restoration. It was during this era that the first cafes appeared, as well as a coffee import tax and the adoption of Western trends.

Omotenashi - a tradition of exceptional hospitality

“Buddy, You did not have to pick me up from Narita, I could have taken the train,” I said after 20 minutes in traffic, flabbergasted at the gesture of picking me up at Narita airport in his Subaru. He would have none of it.

“No, this is our pleasure, it is much better to drive now and tonight we’ll show you around town.” Said Yudai, insisting that this was inevitable from the first texts I sent detailing my visit.

“Town”, in this conversation, was Tokyo, the largest city on earth.

“We’ll find the best Kissaten.” Chimed in Iwashita, Yudai’s wife and speaker of little English.

Yudai is an old friend but not so close that we keep in touch outside of social media. He was a fellow musician synthesizer enthusiast who worked at my favorite coffee shop in Reno. He has an infectious smile and calm demeanor and I always thought his songs perfectly reflected those attributes. When Yudai and his wife Iwashita came to Portland on their honeymoon and stopped by our coffee shop, we got to talking about my upcoming coffee trip to Tokyo and Indonesia. I wouldn’t stop talking about my fascination with Kissatens. Yudai had very little experience with them, but Iwashita loved them. She often studied at a few during her university years.

In a wonderful act of hospitality, they picked me up at the airport, drove me 45 minutes to my hotel in Shibuya, and dropped a pin at our first nearby Kissaten. I settled in and visited the Onsen in my hotel. Ninety minutes later, refreshed with a fresh outfit and a bath, I walked a few blocks to meet them.

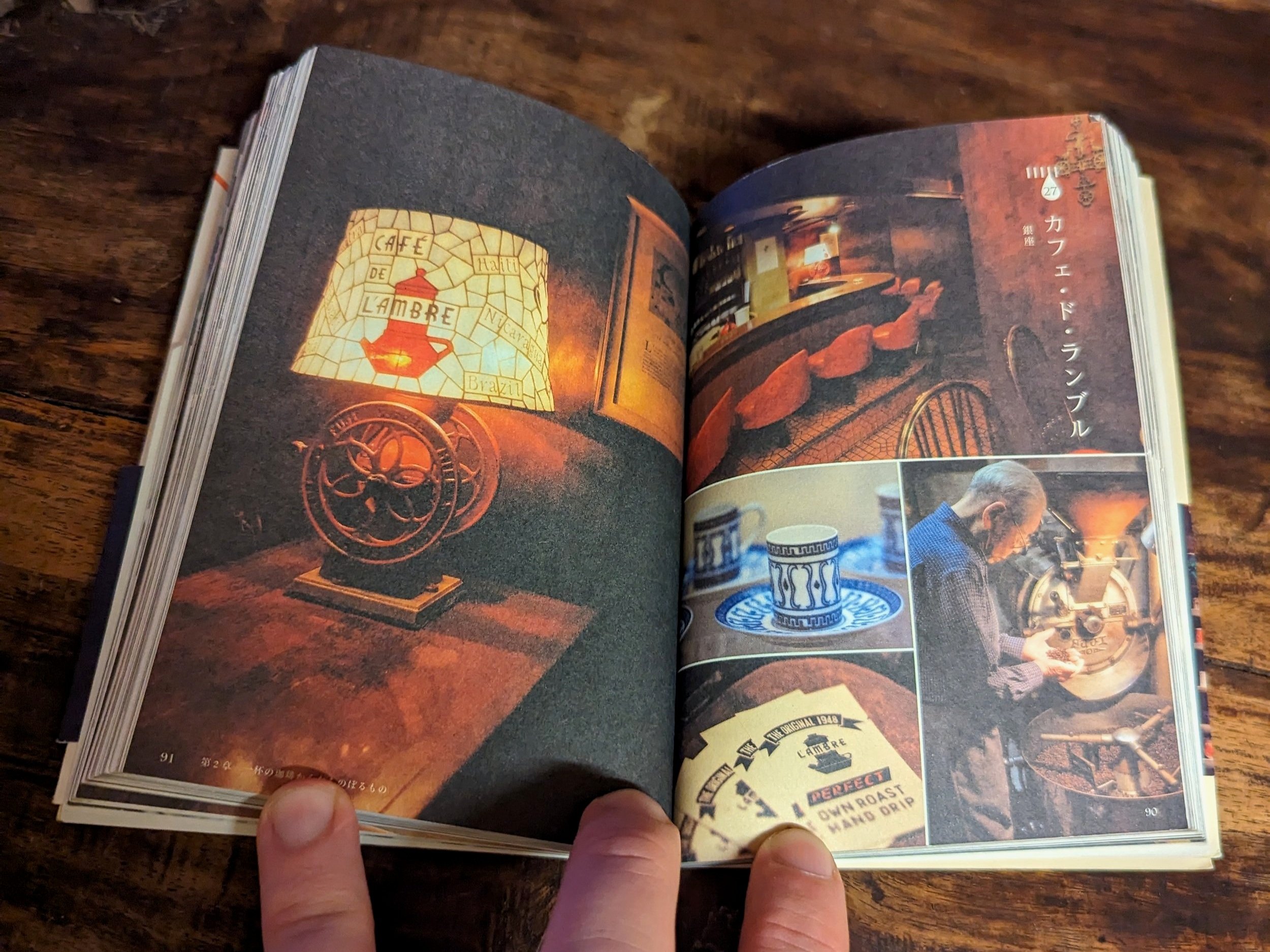

They had spent the time brainstorming and mapping a route of vintage coffee houses created from our text messages. With the help of a manga-sized picture book, our evening would be spent hunting down the retro Kissatens of Shibuya and Ginza.

“Kissaten” as a word is derived from three kanji words “consume + tea + shop” (tea-drinking shop) but is more widely known today for a post-war generation of coffee houses that would be used to venerate Japan’s coffee culture decades later. Coffee shops like Cafe de L’Ambre, Chatei Hatou, Kayaba Coffee, Yokohamaya, and dozens of others have become pilgrimage sites for those of us in the modern coffee business. It was in these Kissatens, that the brewing techniques that fueled coffee’s third wave were studied, augmented, and perfected.

Coffee-centric cafe’s began opening around Tokyo in the 1910’s, but it was in the Showa era that the coffee house was embraced by an enterprising generation of Japanese. Places where people could come and smoke imported cigarettes, listen to imported music, and talk about the war and the future of their country.

Their initial success was integral in the rebuilding of Tokyo and now, decades later, they exist unspoiled by progress, a unique thread in the fabric of an overwhelming metropolis. Many of the Kissatens I visited still operate exactly like they did in the 50s and 60s. The focus remains on providing the ultimate quality under the watchful eye of a coffee master.

In her excellent book, Coffee Life in Japan, author Merry White describes Kissatten’s as being imbued with the spirit of Kodawari. The uncompromising and relentless pursuit of perfection. However, they also echo a time in Japan when the old ways had to make room for the new world. Kissatens are an attempt to retain the ever-important standard of excellence while catering to a world that runs too fast to appreciate the process.

The first years after WWII were a very strange time in Japan. The world had been through hell and Japan was no exception. Gone was Imperial Japan and with it every flammable thing in Tokyo. The construction of the new Japanese State began under the watchful eye of Douglas McArthur until, in 1952, the modern democratic state began in earnest. Tokyo rebuilt itself into a metropolis the size of which the world had never seen before. Population and economic growth skyrocketed, eventually becoming Earth’s largest city, which it still is by most metrics today.

Technique

The Kalita company was formed in Tokyo in 1958, supplying Japan’s coffee houses with locally made coffee wares. Their V60 three-hole ceramic drip, a smaller, faster, more durable take on the German Chemex drip, are ubiquitous in coffee houses around the world and is still the preferred method of the majority of Tokyo’s Kissatens. Kalita also focused on improving the kettle itself to provide maximum control for the barista and leading to the perfection of the pour-over process.

Siphon brewing also gained recognition in Tokyo Kissatens and is surprisingly common in Shibuya where the subtleties of dark Brazilian roasts are amplified in unexpected ways.

Our first stop, a siphon-centric Kissa called “Art Coffee”, had a little of everything. Mid-century teak wood stools and chairs, amber ashtrays, yellow stained glass, and a full menu of “diner” food gave me the feeling we had entered a Midwest-themed diner.

“I swear we were just walking the streets of Tokyo, now we’re at a HoJos in Milwaukee.” I joked.

“Huh?” Yudai asked.

“Um…Like the Cheri’s on Center st.” I say to Yudai, reminding him of a few late nights at a Cheri’s Diner after shows.

The Lowered Serving Area of Art Coffee is Common in Kissatens and provides a Chef’s Table View.

We ordered three Siphon brewed coffees and sat at the wrap-around Formica bar where the kitchen area is slightly lowered. I love this design. It is very common in Kissatens that the barista area behind the bar is lowered. This has become one of my favorite things about the coffee-going experience in Tokyo. This small detail sets the sitting customer eye to eye with the coffee master and allows the customer to observe the subtleties of the process.

The siphon coffee was served demitasse and on initial sips reminded me of life’s first cups of coffee at the window factory my Dad worked at when I was little. The way aroma would fill my Dad’s office and waft its way into the break room where it mingled with the cigarette smoke.

Luckys

Here we pause to speak of cigarettes. Specifically, the insane odor of unfiltered Lucky Strikes, another post-war fad that resonated with that generation and still, unfortunately, is common today. I experience nausea around cigarettes and every single Kissaten I visited over my days in Tokyo was loaded with amber ashtrays and smokers filling them up. Honestly, it made the subtleties of the coffee flavors hard to decipher. I’d have to suck it up for Tokyo, but I would leave many cups unfinished as my body insisted on fresh air.

Sensing my nicotine-induced discomfort, Yudai asked for the check. We had many cups ahead of us, no reason to get nauseous now.

“Everybody that age smokes.” Said Yudai, who does not. “My dad, my mom, my grandparents.”

“They must know it’s awful for you?” I asked.

“Of course, but it’s part of their freedom.” He said.

As an American who grew up bombarded with cigarette advertising in magazines, that made sense. Madison Avenue made it their mission that the whole world would associate smoking with the freedoms democracy afforded and Japan was one of their major success stories. For decades, capitalism “worked” in Japan faster and stronger than anywhere else on Earth.

This smokey detail also highlighted what coffee meant to this place. It was the drink of democracy and the bill of goods sold with it. A business drink for the Nikkei index, a forward-looking drink that provides bursts of energy needed to make business deals. It was the brew of their new, ever-expanding free market.

With one cup down, we were on the move to the busy areas of Shibuya and Shinjuku, to look skyward and marvel at the fruits of expansion.

Without Yudai and Iwa, I don’t know how successful my trip would have been. Tokyo, more than any other major city, does not cater to English-only speakers. It’s a refreshing thing to ponder now, but I was embarrassed at how off guard I was at the lack of assistance.

Luckily, with Yudai and Iwa, I would be able to have several full Kissaten experiences on the first night and that would allow me to wander in awe around the city for the rest of my time here. As a traveler, there is no greater suggestion I can give than that of an unorganized exploration of Tokyo. You will be overwhelmed, you will get lost and you will go to sleep having been thrilled with a truly authentic travel experience.

TO BE CONTINUED…